When building a project, it’s very likely that we will install third-party packages from npm to offload some tasks. On that topic, we know there are two major types of dependencies: dependencies (prod) and devDependencies (dev). In our package.json, it might look something like this:

{

"name": "my-cool-vue-components",

"dependencies": {

"vue": "^3.5.15"

},

"devDependencies": {

"eslint": "^9.15.0"

}

}The main difference is that devDependencies are only needed during the build or development phase, while dependencies are required for the project to run. For example, eslint in the case above only lints our source code; it’s no longer needed when we publish the project or deploy it to production.

The concept of dependencies and devDependencies was originally introduced for authoring Node.js libraries (those published to npm). When you install a package like vite, npm automatically installs its dependencies but not its devDependencies. This is because you are consuming vite as a dependency and don’t need its development tools. So, even if vite uses prettier during its development, you won’t be forced to install prettier when you only need vite in your project.

As the ecosystem has evolved, we can now build much more complex projects than ever before. We have meta-frameworks for building full-stack websites, bundlers for transpiling and bundling code and dependencies, and so on. Node.js became a lot more than just running JavaScript code and packages on the server side.

I’d roughly categorize projects into three types:

- Apps: Websites, Electron apps, mobile apps, etc. Here,

package.jsonprimarily keeps track of dependency information, and the app itself is never published to npm. - Libraries: Packages designed to be published to npm, then installed and consumed by other projects.

- Internal: Packages used within monorepos that are never published.

Fundamentally, the distinction between dependencies and devDependencies only truly makes sense for libraries intended for publication on npm. However, due to different scenarios and usage patterns, their meaning has extended far beyond the original purpose.

Tools often overload the meaning of dependencies and devDependencies to fit various scenarios, aiming for sensible defaults and better Developer Experience.

For example, Vite treats dependencies as "client-side packages" and automatically runs pre-optimization on them. Build tools like tsup, unbuild, and tsdown treat dependencies as packages to be externalized during bundling, automatically inlining (bundling) anything not listed in dependencies.

While these conventions certainly simplify things in most cases, they also force dependencies and devDependencies to wear multiple hats, making it harder to grasp the purpose of each package.

If we see vue listed in devDependencies, it could mean several things:

- We are inlining/bundling it.

- We are only referencing its types.

- We use it solely for testing.

- We have it to enable IDE IntelliSense.

- Or something else entirely.

Simply classifying packages as dependencies or devDependencies doesn’t provide the full picture of that package’s purpose without external documentation (also note that package.json doesn’t support comments).

Categorize Your Dependencies #

Let’s forget about dependencies and devDependencies for a moment, how might we categorize our dependencies? Here are some rough ideas I could come up with:

test: Packages used for testing (e.g.,vitest,playwright,msw).lint: Packages for linting/formatting (e.g.,eslint,knip).build: Packages used for building the project (e.g.,vite,rolldown).script: Packages used for scripting tasks (e.g.,tsx,tinyglobby,cpx).frontend: Packages for frontend development (e.g.,vue,pinia).backend: Packages for the backend server.types: Packages for type checking and definitions.inlined: Packages that are included directly in the final bundle.prod: Runtime production dependencies.- …

Categorization might differ between projects. But that point is that dependencies and devDependencies lack the flexibility to capture this level of detail.

This thing had been bothering me for a while, though it didn’t feel like a critical problem needing immediate resolution. Only until pnpm introduced catalogs, opening up possibilities for dependency categorization we never had before.

PNPM Catalogs #

PNPM Catalogs is a feature allowing monorepo workspaces to share dependency versions across different packages via a centralized management location.

Basically, you add catalog or catalogs fields to your pnpm-workspace.yaml file and reference them using catalog:<name> in your package.json.

# pnpm-workspace.yaml

catalog:

vue: ^3.5.15

pinia: ^2.2.6

cac: ^6.7.14// package.json

{

"dependencies": {

"vue": "catalog:",

"pinia": "catalog:",

"cac": "catalog:"

}

}Or with named catalogs:

# pnpm-workspace.yaml

catalogs:

frontend:

vue: ^3.5.15

# We locked the version for some reason, etc.

pinia: 2.2.6

prod:

cac: ^6.7.14// package.json

{

"dependencies": {

"vue": "catalog:frontend",

"pinia": "catalog:frontend",

"cac": "catalog:prod"

}

}During installation and publishing, pnpm automatically resolves dependencies to the versions specified in the catalogs. While it’s originally designed for managing version consistency across monorepos, I found Named Catalogs are also a great way to also categorize dependencies. As shown above, we can categorize vue and cac into different catalogs even though they both presented in dependencies. This information makes version upgrade easier and would help on reviewing dependency changes.

A nice bonus: you can use comments in

pnpm-workspace.yamlto share additional context with your team.

Tooling Support #

Given that catalogs are still quite new, this shift requires better tooling support. A significant pain point for me on this was losing the ability to see a dependency’s version at a glance in package.json when using catalog:<name>.

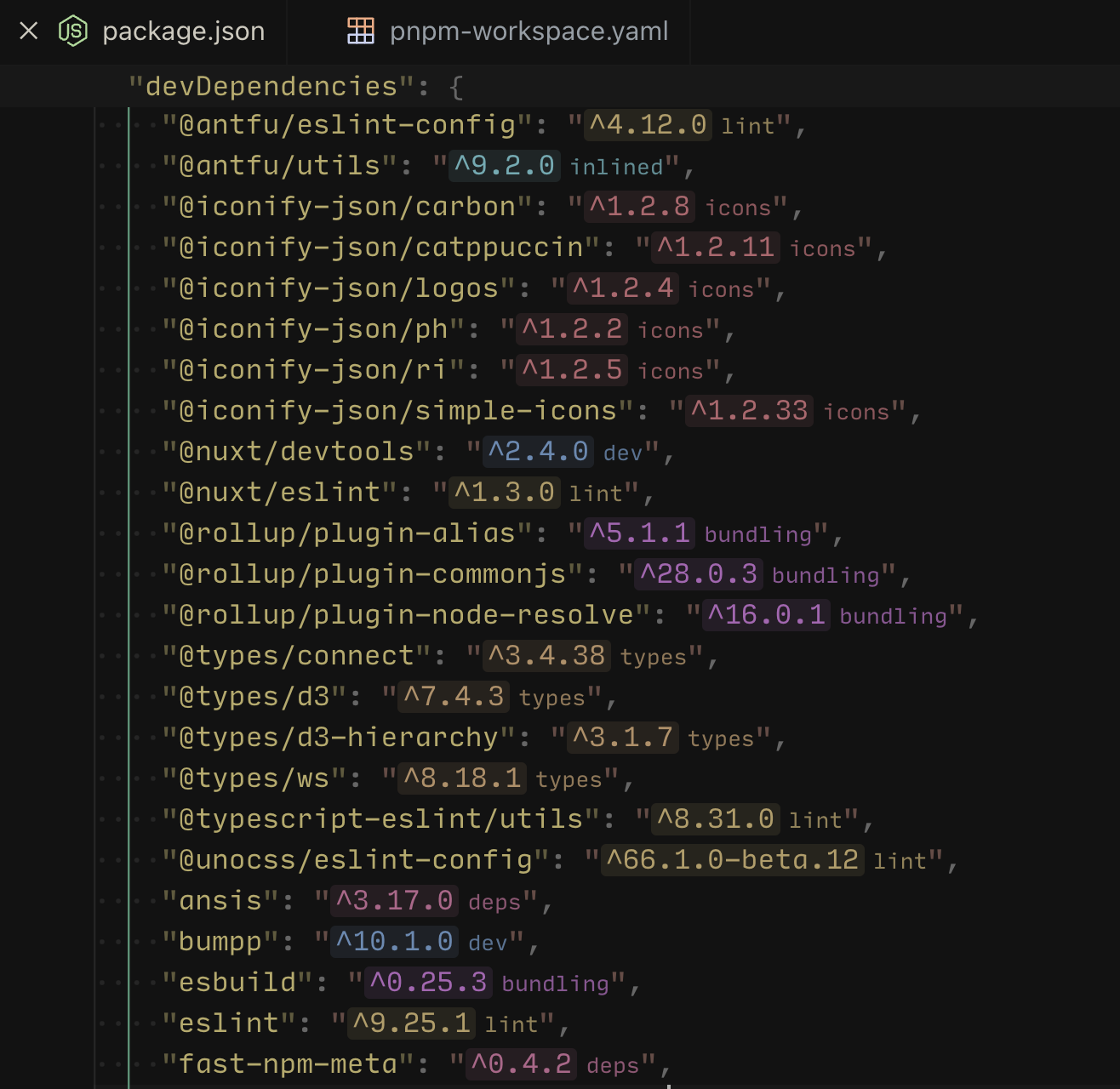

To address this, I created a VS Code extension, PNPM Catalog Lens, which displays the resolved version inline within package.json.

It also adds distinct colors to each named category for easier identification. This gives us the categorization and centralized version control without significantly impacting DX.

Since versions move to pnpm-workspace.yaml, CLI tools would need to make some integrations to support this. So far, we’ve adapted the following tools:

taze: Checks and bumps dependency versions, now supporting reading and updating versions from catalogs.eslint-plugin-pnpm: Enforces using catalogs for all dependencies inpackage.json, with auto-fixes.- If you use

@antfu/eslint-config, enable this by settingpnpm: true.

- If you use

pnpm-workspace-yaml: A utility library for reading and writingpnpm-workspace.yamlwhile preserving comments and formatting.node-modules-inspector: Visualizes yournode_modules, now labeling dependencies with their catalog name for a better overview of their origin.nip: Interactive CLI to install packages to catalogs

Looking into the Future #

Currently, I see the value of categorize dependencies is mainly for better communication and easier version upgrade reviews. However, as this convention gains wider adoption and tooling support improves, we could integrate this information more deeply with our tools.

For example, in Vite, we could gain more explicit control over dependency optimization, decoupling it from the dependencies and devDependencies fields:

// vite.config.ts

import { readWorkspaceYaml } from 'pnpm-workspace-yaml'

import { defineConfig } from 'vite'

const yaml = await readWorkspaceYaml('pnpm-workspace.yaml') // pseudo-API

export default defineConfig({

optimizeDeps: {

include: Object.keys(yaml.catalogs.frontend)

}

})Similarly, for unbuild, we could explicitly control externalization and inlining without manually maintaining lists in multiple places:

// build.config.ts

import { readWorkspaceYaml } from 'pnpm-workspace-yaml'

import { defineBuildConfig } from 'unbuild'

const yaml = await readWorkspaceYaml('pnpm-workspace.yaml')

export default defineBuildConfig({

externals: Object.keys(yaml.catalogs.prod),

rollup: {

inlineDependencies: Object.keys(yaml.catalogs.inlined)

}

})For linting or bundling, we could enforce rules based on catalogs, such as throwing errors when attempting to import backend packages into frontend code, preventing accidental bundling mistakes.

This categorization could also provide valuable context for vulnerability reports. Vulnerabilities in build tools might be less severe than those in dependencies shipped to production.

…and so on.

I’ve already started migrating many of my projects to use named catalogs(node-modules-inspector for example). Even outside monorepos, the ability to categorize dependencies is a compelling reason to adopt to pnpm catalogs. I consider this an exploratory phase where we’re still discovering best practices and improving tooling support.

So, that’s why I’m writing this post: to invite you to consider this approach and try it out. We’d love to hear your thoughts and how you would utilize it. I look forward to seeing more patterns like this emerge, helping us build more maintainable projects with a better DX. Thanks for reading!